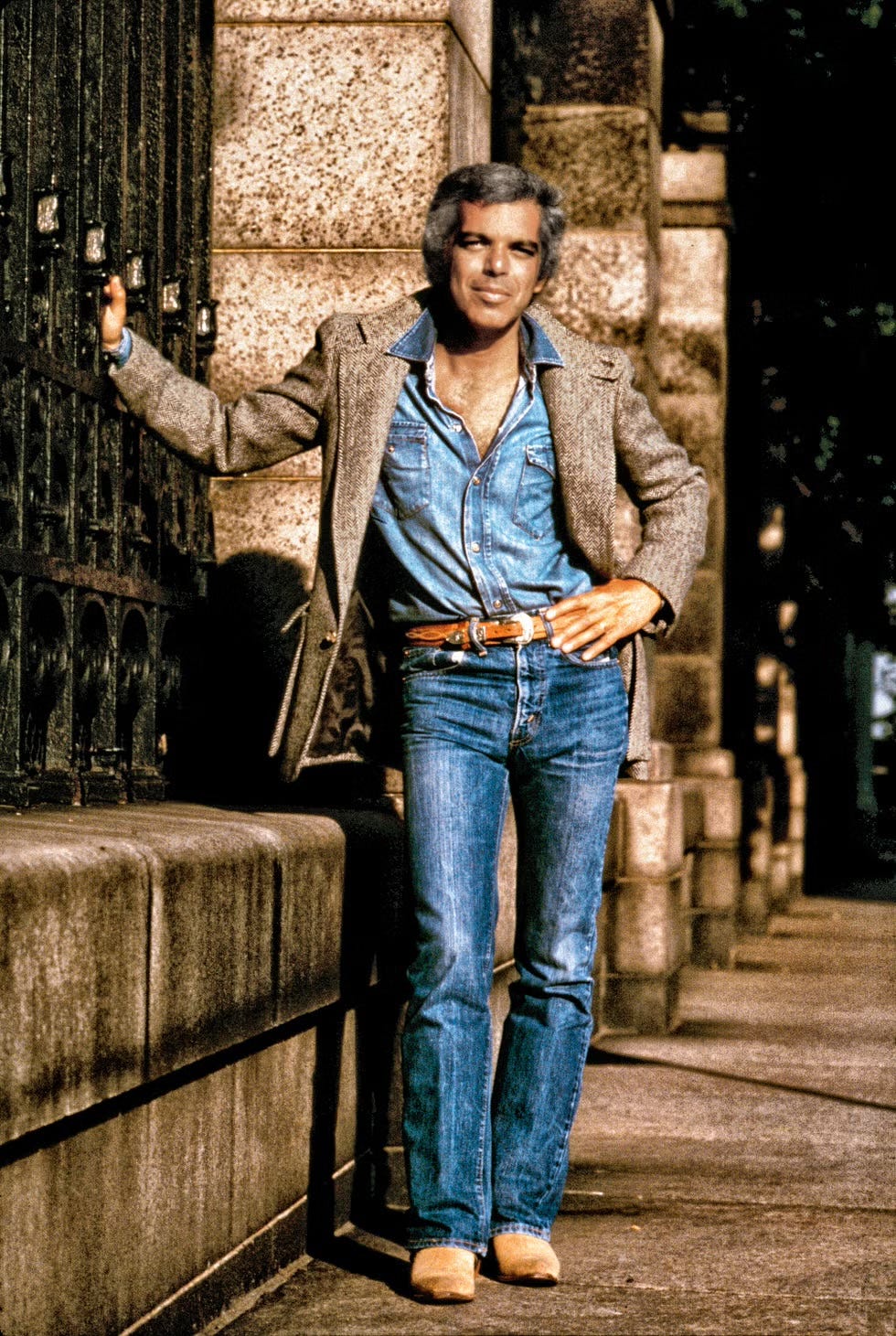

When Ivy went west, there are a few key influences worth noting. Hollywood in the ‘60s, for one—a mix of fashionable experimentation and a natural evolution toward something better suited to the sun-drenched hills of Southern California. And of course, Ralph Lauren. Actually, mostly Ralph, I’d say.

Double denim with a repp tie? Boat shoes with a Type III jacket? Ralph Lauren didn’t just make Ivy aspirational—he made all facets of American style feel like they belonged in the same wardrobe. Ivy had to meet western, just as much as western had to head east.

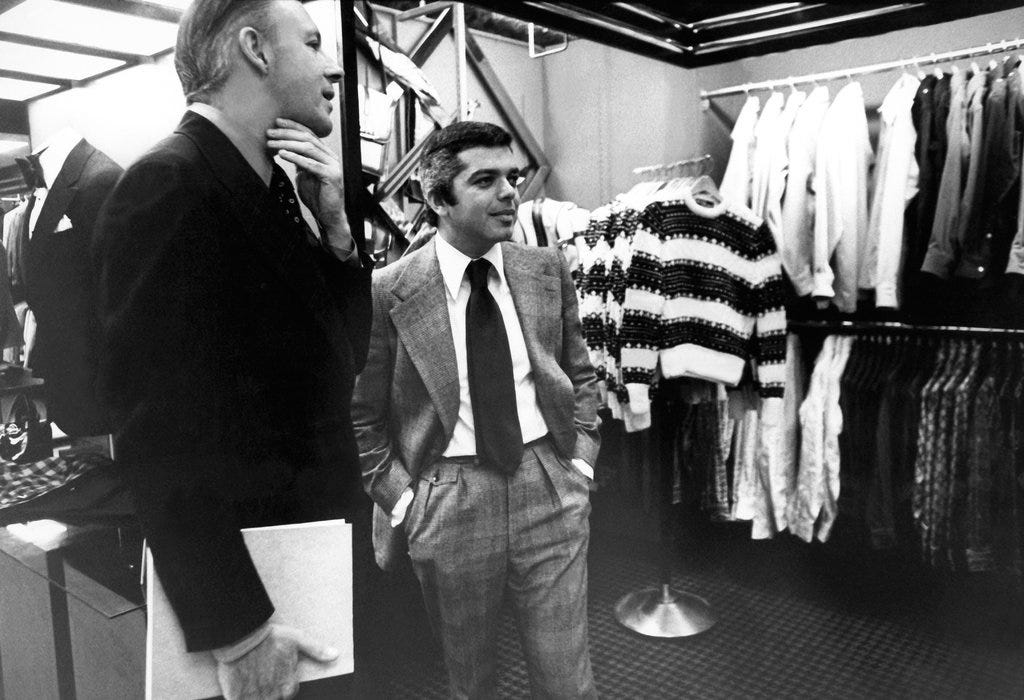

It’s 1971, Upper East Side, Manhattan. Nestled at 867 Madison Avenue, Ralph Lauren opens his first standalone store.

Aspiration hits you the moment you step through the doorway. The interior feels more like a gentleman’s club than a shop — dark wood, Persian rugs, and a quiet confidence. The only way to join the club? Wear the clothes.

Ralph Lauren wasn’t just selling shirts and suits. He was selling the American Dream — every version of it. At home, at the office, and on holiday.

By 1971, spaghetti westerns had already peaked in the U.S., but their legacy lingered. The genre had taken American icons — Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef — and sent them to Italy, where they cemented their status as global cool. The clothes were tougher, the attitude sharper. They didn’t just wear the American dream — they became it.

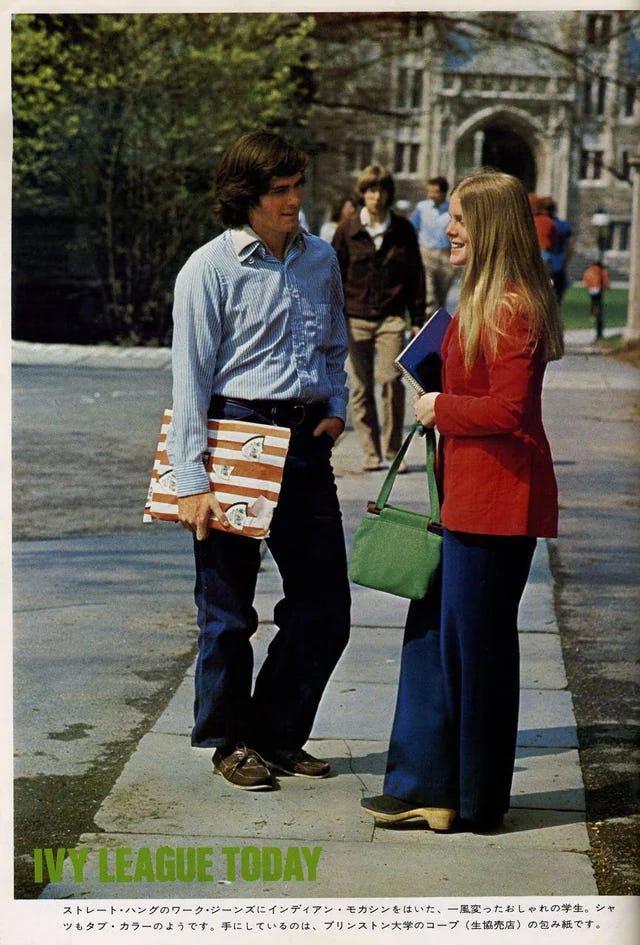

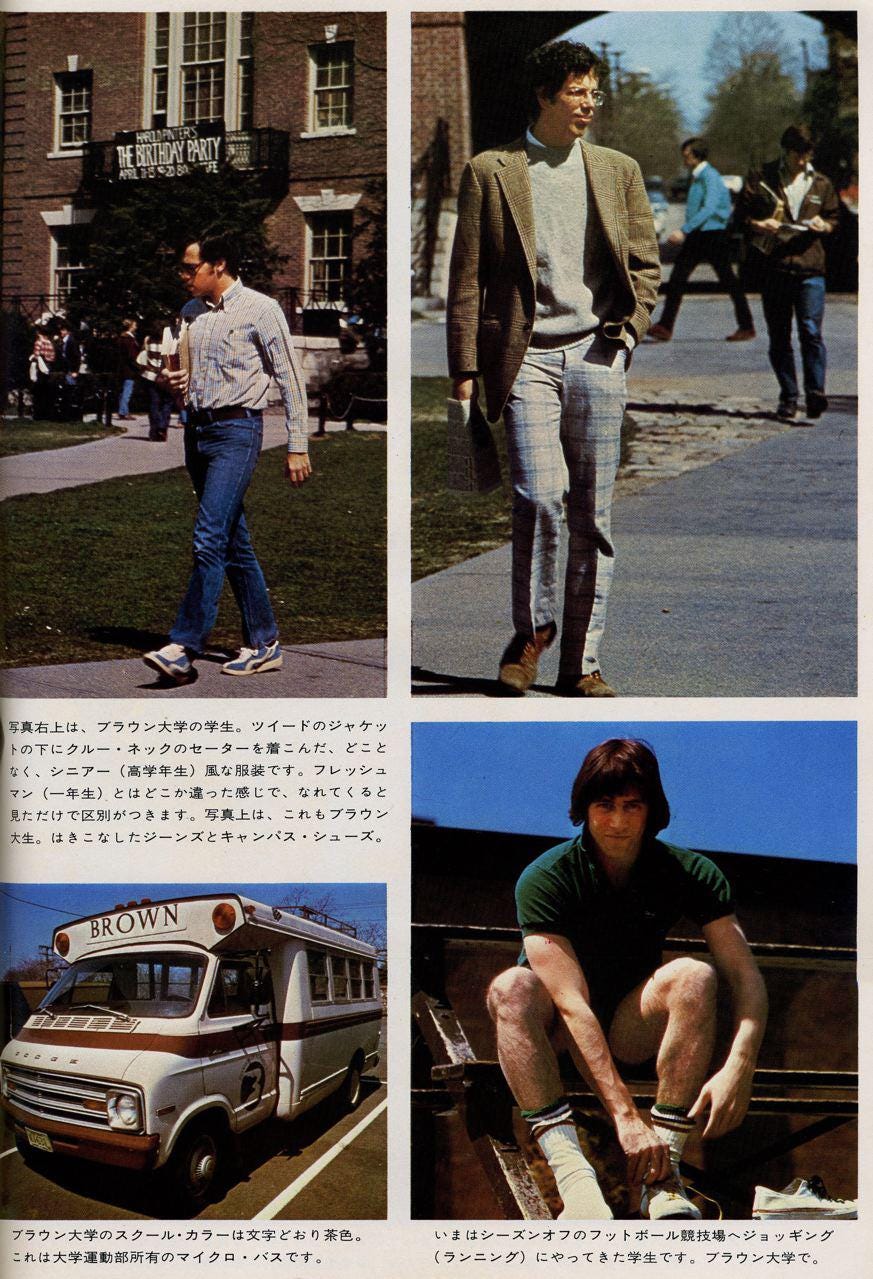

Through the 1970s, Ivy style underwent a major transformation. The institutions that once shaped and reflected it—Harvard, Yale, Princeton—were changing too.

These schools began shifting toward a more meritocratic model. Admissions became more academically focused and inclusive of students from diverse socioeconomic, racial, and religious backgrounds. What had long been a reflection of the American upper class was opening up.

With that shift, the style changed too. Dressing to look upper class was no longer the point. In many cases, it was actively rejected.

Ralph Lauren remained relevant not by abandoning his vision, but by expanding it. His version of the American dream wasn’t limited to the Ivy League quad—it stretched across the entire country. Western style, in particular, became one of the defining influences on American menswear. Few understood that better than Ralph.

“True Grit”

Post-1960s Ivy began to shed some of its original "dressed-up" principles, those buttoned-up but casual-for-the-time standards, and gradually welcomed pieces with grit. Though it started as a polished look, Ivy was always a quiet form of rebellion, and the introduction of Western workwear continued that tradition: dressing against expectations.

Rather than aiming to impress a hierarchy, wearers began to lean into what felt real—durable, comfortable, honest. Ivy’s evolution mirrors a broader shift in how society approached clothing: less about status, more about identity. Western influences didn’t replace the East Coast silhouette. They textured it.

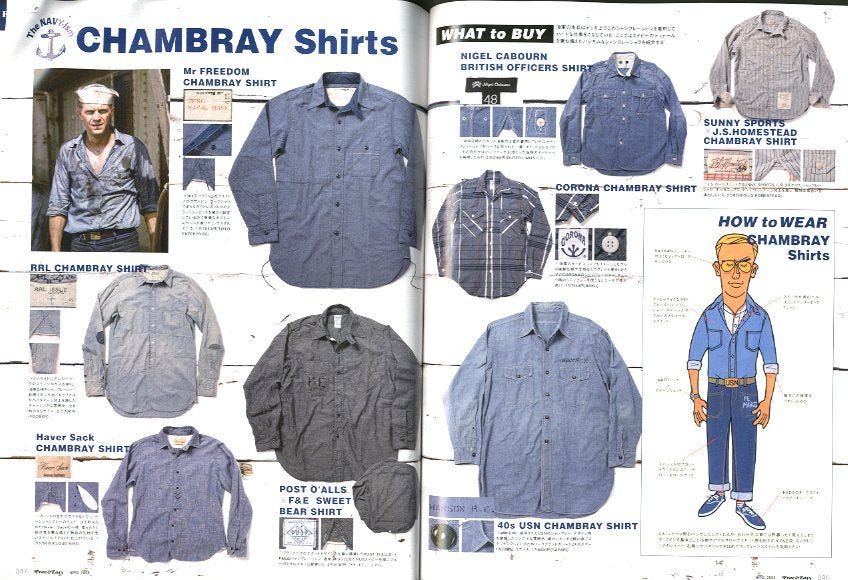

We can’t talk about the merging of Ivy, prep, and Western style without giving a significant nod to Japan. This fusion lives and breathes through Amekaji, short for “American casual,” a Japanese interpretation of American traditional style. Amekaji isn’t just Ivy. It draws equally from vintage workwear, military surplus, and rugged denim, blending them all into one cohesive, endlessly reinterpreted look.

Think of it as the Japanese-American wardrobe, not in heritage, but in vision. A style built by curating, refining, and remixing American classics into something uniquely their own.

What started as rebellion became tradition. What was once East Coast became global. And today, when someone pulls on a denim chore coat over a tie, or slips penny loafers under raw selvedge cuffs, they’re not just getting dressed. They’re participating in a decades-long dialogue between comfort and class, heritage and reinvention. Ivy didn’t fade. It adapted. And maybe that’s what keeps it so quietly powerful.