All the gear, no idea.

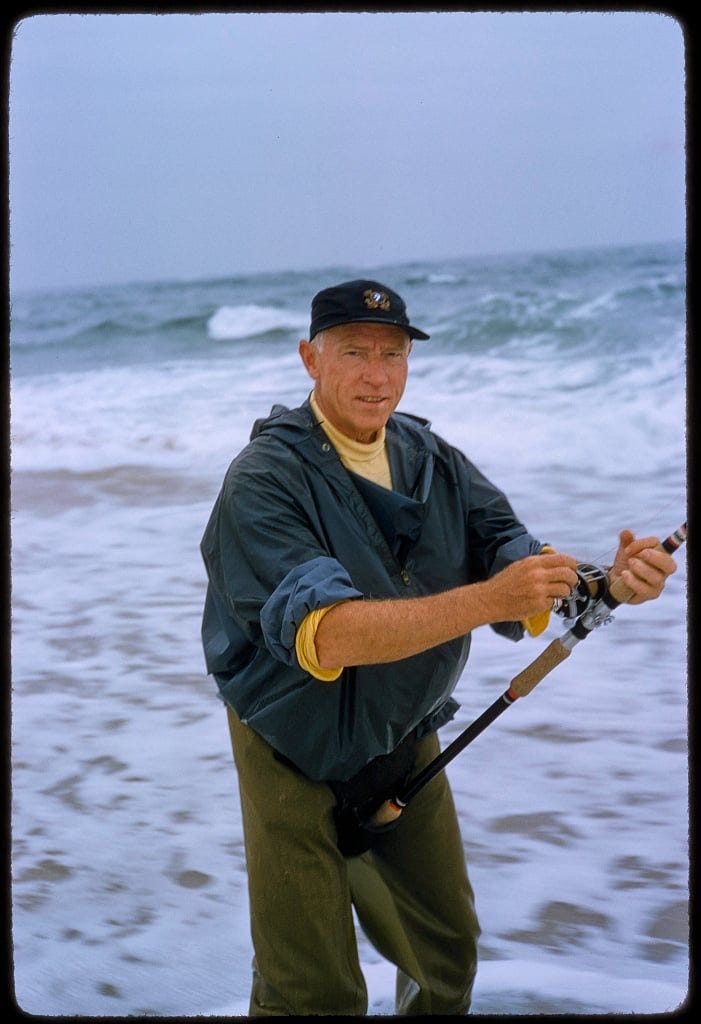

Dressing like a fisherman with no plans to fish.

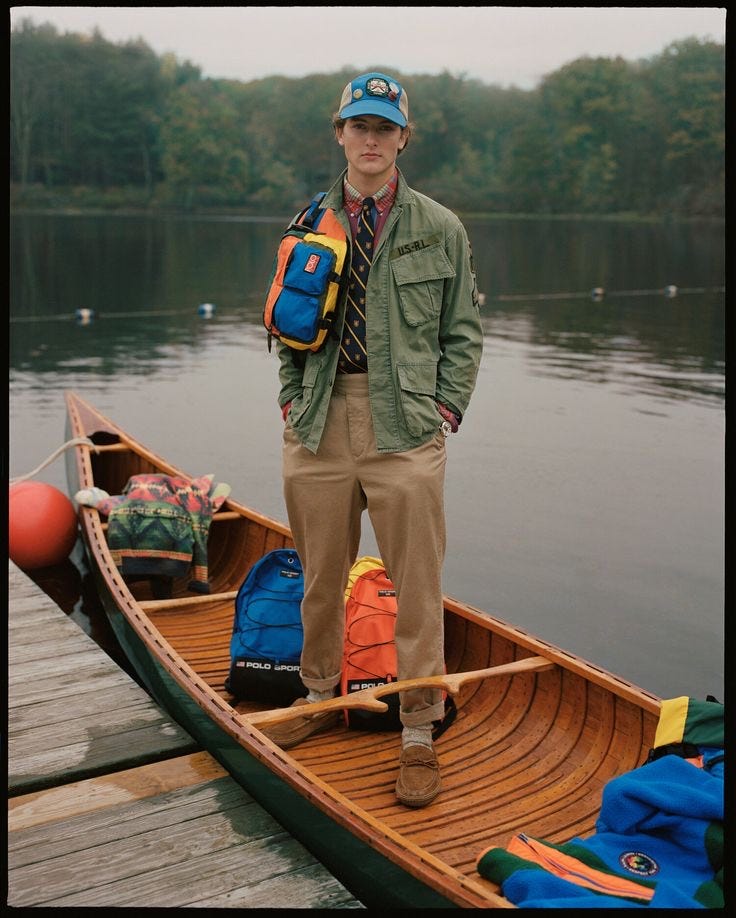

Fishing is part of that East Coast elite leisure look — rugged Ivy mixed with something more technical, practical, and functional.

I live in a landlocked city. So why am I dressed like I’m about to head out on a boat to catch the prized lunker? Because it looks good, that’s why.

Ivy style was born out of aspiration. Think of middle-class American college students imitating what they imagined Oxbridge elites were wearing — dressing in ways that made them seem sophisticated, interesting, and like they’d attended a well-established college, even if they hadn’t.

I wouldn’t say that’s what Ivy is about today. The look may have stayed recognisable — evolved, even — but I don’t think people are still dressing to suggest they went to a certain school or to hint at a high IQ. Still, that original sense of aspiration is baked into the foundations of Ivy, and it’s part of what’s made it such a fixture in contemporary menswear.

Beyond the college staples, Ivy style also borrowed from upper-middle-class leisurewear — kit worn for pastimes like polo, rugby, and of course, fishing. These pieces weren’t worn to suggest you were a keen fly-fisher, but to quietly nod to that aspirational American life.

One of my favourite pieces from this look is the fishing vest. Practical, comfortable, and versatile — a perfect balance, if I do say so myself.

For the modern gent lugging a phone, wallet, keys, headphones, car park ticket, vape, maybe even a coffee stamp card — why wouldn’t you wear something designed for utility?

Swap the floats for your everyday carry — you’re basically a walking tote bag.

So much of what we wear is rooted in utility. I’d argue the best clothing is. The Baracuta golf jacket, anyone? Jeans made for cowboys by Wrangler? Most of your wardrobe, whether you realise it or not, has its roots in workwear or uniform.

So here I am — no fishing licence, no rod, no bait, nowhere to take a boat… and no boat, of course. But I’m dressed like a proud member of the Rainbow Trout Alliance. Why? Because it just works.

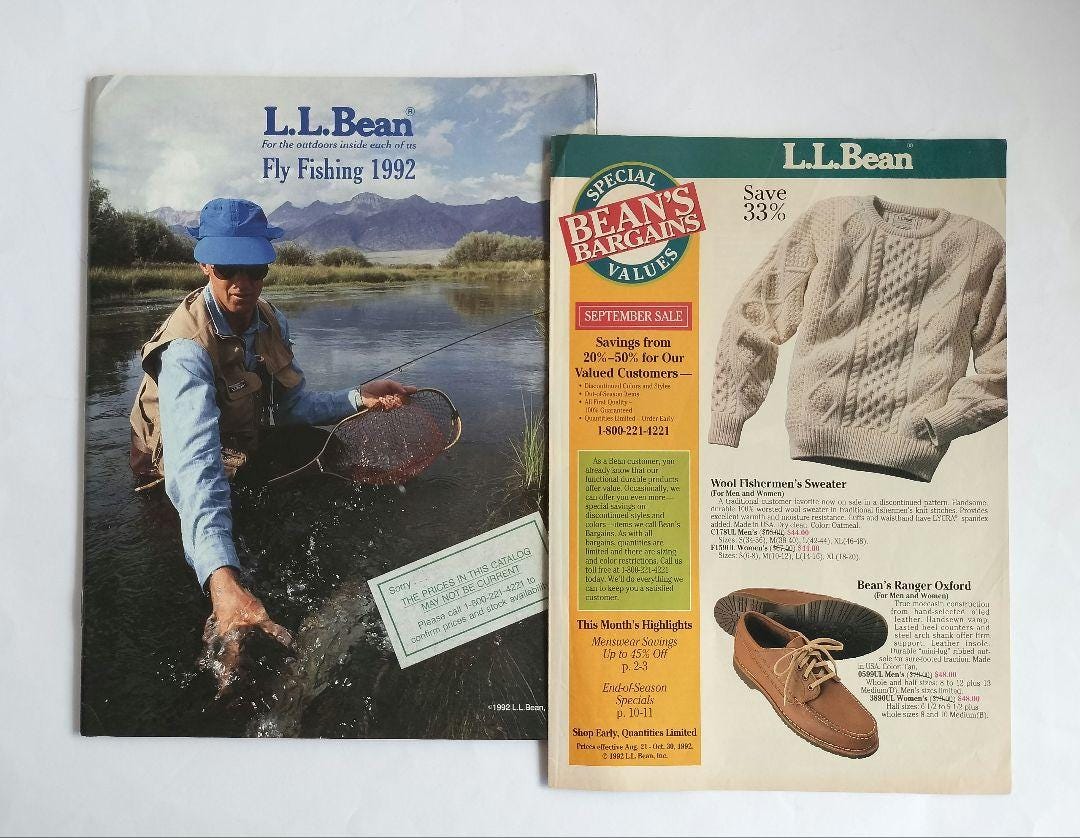

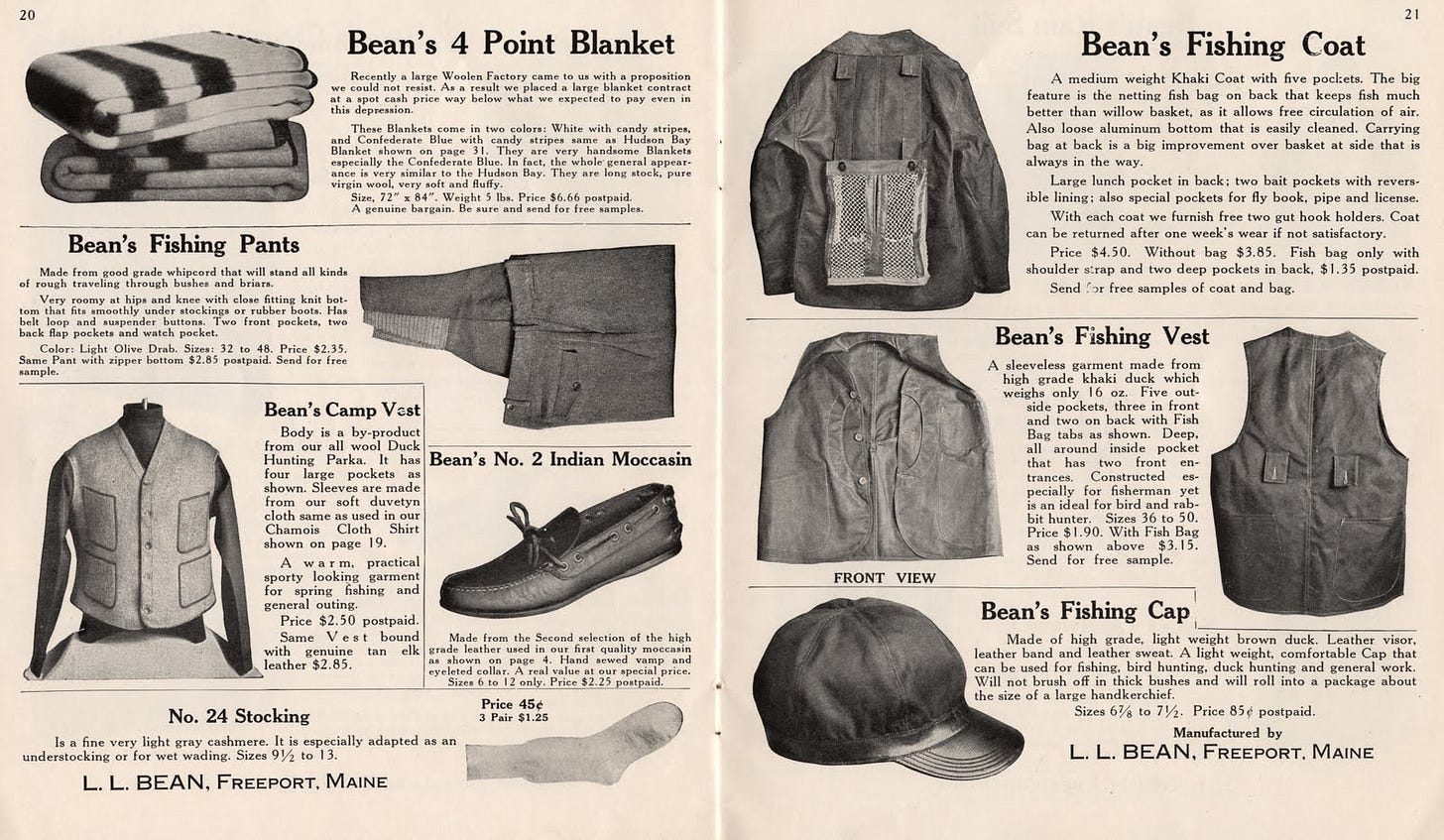

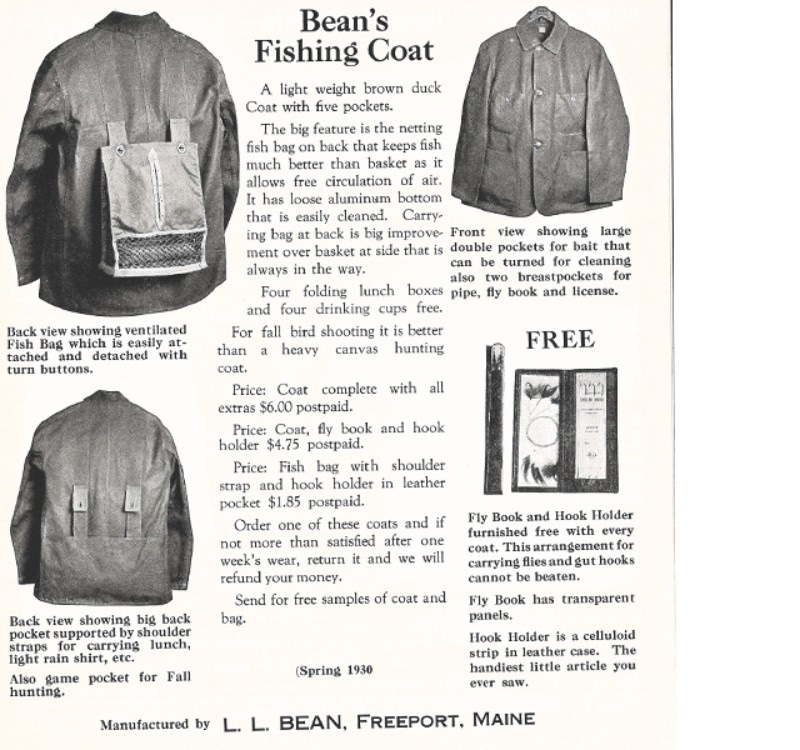

L.L. Bean feels like the brand that best represents this look — clothing made for the outdoors, but with real style. The Boat and Tote has been fully adopted into the Ivy canon, but Bean is much more than that. It’s apparel designed for the elements — built to last through all sorts of terrain and weather. The brand from Freeport, Maine, is the definition of Northeast American practicality.

The history of L.L. Bean says it all. Ivy style has never really been about originality — it’s always pulled from elsewhere, repurposing and reinterpreting along the way.

Take the Boat and Tote. Originally designed in 1944 to carry ice, it became popular with college students in the ’50s and ’60s who used it to carry books. Rugged canvas, solid stitching — it fit right in with their look and stood up to daily use.

And that’s the thing — L.L. Bean wasn’t fashion. It was functional. But it had that quiet New England ruggedness that Ivy style thrives on. In many ways, it was anti-fashion — anti–fast fashion. Durable, understated, and a subtle nod to a certain kind of Northeast heritage and privilege.

And if we’re talking fishing aesthetics, L.L. Bean has long led the way — fly-fishing jackets, vests, field coats, gear designed with genuine purpose. But there’s style in that purpose, too.

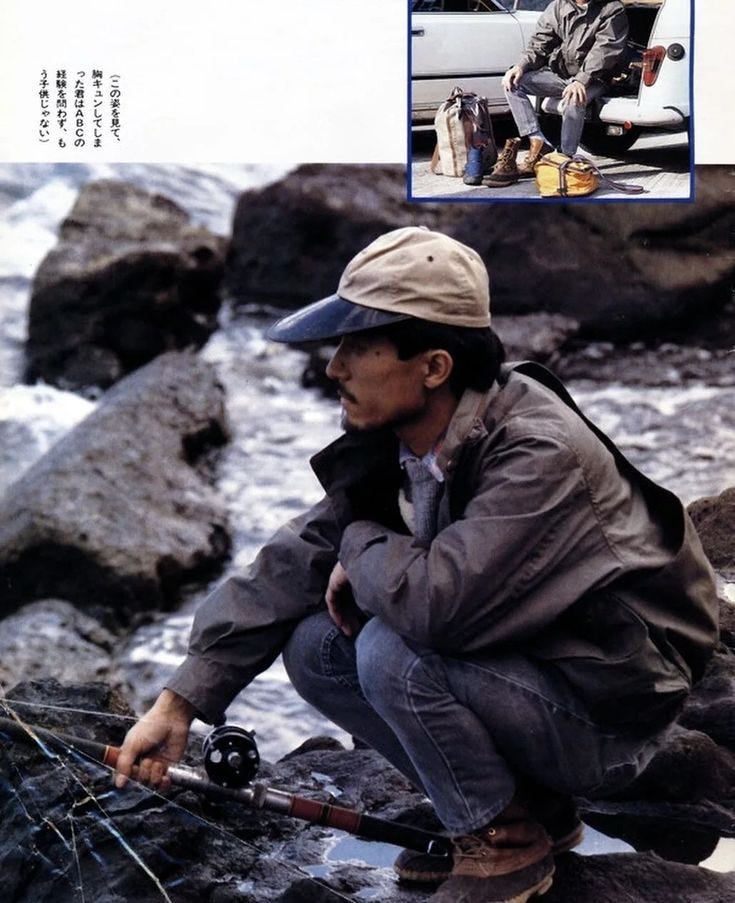

And it’s not just the old-school names. Brands like Beams Plus and Engineered Garments have explored this same space for years, blending outdoorswear and Ivy with Japanese sensibility.

Even Fera — a relative newcomer — recently dropped a whole collection built on this exact aesthetic: practical, unfussy, rooted in utility.

I don’t intend to fish anytime soon. But I do intend to dress like I do. And that’s the beauty of this kind of clothing. If it was made to serve a purpose — for fishing, outdoor pursuits, or just being out in the elements — chances are, it’s going to be fantastic for everyday life too.